The airport business model can be highly lucrative.

On the supply side, barriers to entry are high. Enormous capital investment is required, and airport development is often limited by environmental, social, and political complexities – especially in Western countries. Witness the case of Western Sydney Airport: the Australian government originally announced Badgerys Creek as the location for Sydney’s second airport in 1986, and it’s on track to commence operations in 2026.

On the demand side, airport traffic volumes have demonstrated strong and relatively predictable long-term growth (notwithstanding temporary shocks like 9/11 or COVID-19). Airport patrons often have a high propensity to spend – many are relatively wealthy and/or travelling for business. More widely, the economic vibrancy of the airport precinct attracts plenty of related businesses – freight, hotels, educational institutions etc. Given that airports typically have large land holdings, this creates attractive property development opportunities for the airport to complement its core activities.

So how do airports generate income?

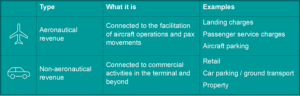

At the simplest level, airport revenue is delineated between aeronautical and non-aeronautical activities.

For many airports, non-aeronautical revenue has become a larger part of the overall revenue mix in recent decades. Whereas aeronautical revenue is typically regulated in some form (whether heavy- or light-handed regulation) non-aeronautical revenue is typically unregulated, offering the prospect of higher returns. This has been a strong source of value creation as airports have privatised (and corporatised, even if remaining in public hands).

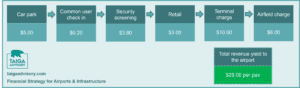

Let’s look from a practical perspective. The passenger’s airport journey is basically a value chain, driving the airport’s revenue base. Take this simple illustrative example showing a hypothetical airport’s revenue yield derived from a departing passenger:

Driving growth in yield (typically measured as income per passenger) is integral to successful airport financial strategy. This includes capturing the synergies between each revenue stream. A basic example – securing new long-haul international services might strengthen retail yield because passengers arrive earlier, spending more in the terminal before departure. Car parking revenues might also be boosted by increased length of parking stay (because pax are travelling further, for longer trips). In this manner, overall yield can be driven higher as pax volumes grow and diversify.

Growth in airport traffic, plus growth in airport revenue yield – it’s a simple yet successful formula.

Understanding revenue yield is crucial for any airport. A data driven approach is crucial in developing strategies tailored for each revenue stream. Benchmarking is invaluable in this regard.

Beyond headline yield, deeper analysis sheds light on customer behaviour and value drivers. Car park performance, for example, requires investigation of a) the penetration rate (the proportion of passengers that are parking) and b) the spend rate (the value of each parking transaction) within each car park area.

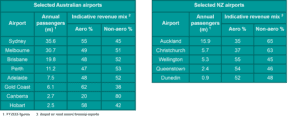

Every airport has a unique revenue mix – depending on the airport’s traffic profile, competitive dynamics, catchment area etc. A snapshot of major Australian and New Zealand airports is shown below:

Consider the following examples (not exhaustive!) showing how airport revenue profiles differ:

- Perth Airport achieves high yields in ground transport, helping generate a relatively high non-aeronautical revenue share. Perth’s ground transport yield is comfortably the strongest of the “Big 4” Australian airports – underpinned by robust car parking penetration rates, spend rates and significant parking capacity.

- Queensland Airports (owner of Gold Coast Airport) generates a relatively low ground transport yield. As one of Australia’s premier tourism destinations, Gold Coast is a predominantly “inbound” market. This would be expected to impact the relative size of car parking revenues, compared to airports with a more even outbound/inbound split. It’s similar for Queenstown Airport in New Zealand, with a car parking yield substantially below many other NZ airports – consistent with Queenstown’s heavily inbound traffic profile.

- Sydney Airport achieves the strongest retail yields in Australia – reflecting its status as Australia’s largest international gateway and location in Australia’s wealthiest city. As an extreme comparison, Hobart’s retail yield is roughly 80% lower than Sydney – serving a much smaller market with domestic services only. The same trend is seen with Auckland Airport.

- Canberra Airport’s non-aeronautical revenues are driven by an exceptionally large property portfolio, comprising three significant business parks. For airports in general, these assets can offer revenues with less (or no) correlation to airport traffic volumes, helping de-risk the overall revenue base.

Knowing how to drive value from aero and non-aero activities is fundamental to any airport’s long-term financial strategy. Airports should build a long-term revenue “roadmap” that examines the optimal long-term revenue profile (aero / non-aero etc.) and target yields for each segment – underpinning the airport’s financial forecast and commercial strategies.

Taiga Advisory are experts in airport financial strategy and CFO consulting. We support airports in all aspects of financial management, strategy and commercial planning. With deep experience in airport financial management, we provide practical, hands-on support. Get in touch to learn more.